Noah Brier | August 5, 2025

The Kessler Syndrome Edition

On space junk, cascading collisions, and why orbit is starting to look like a highway with no cleanup crew.

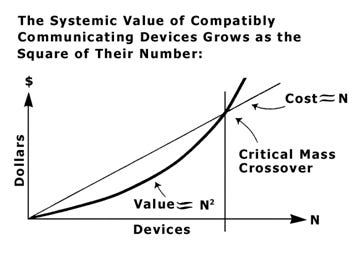

Noah here. Network effects have long taken over the business world. There’s not an HBS grad or Big 4 consultant who doesn’t keep the term on the tip of their tongue. Every pitch deck, strategy memo, and IPO filing cites the power of n².

The idea, as we know it, comes from Bob Metcalfe, who came up with his “law” in 1980, while trying to sell Ethernet cards at his company, 3Com. The problem he faced was simple to articulate and incredibly hard to solve: why buy a network card when nobody else has one? His insight came on a 35mm slide showing that network value grows with the square of its users. Two phones make one connection, five phones make ten, and a hundred make 4,950.

Why is this interesting?

Because what if you found a network that worked against itself as it grew?

That’s low Earth orbit, where satellites abound. Every new satellite adds value to its own network—Starlink needs more satellites to cover more ground for its users—but also adds risk to everyone else with equipment up there. The more stuff we put into orbit, the more that stuff might crash into each other, creating bits of space debris that can then crash into more stuff. (If this sounds a bit like Gravity with Sandra Bullock, you’re right, though that’s a Hollywood-ified version that doesn’t exactly follow the laws of physics.)

The term for this kind of space junk cascade is Kessler syndrome. In 1978, NASA scientist Donald Kessler predicted that “random collisions between objects large enough to catalogue would produce a hazard to spacecraft from small debris that is greater than the natural meteoroid environment.” His math showed that collisions create debris, debris creates more collisions, and eventually, you get exponential growth in destruction. It’s Metcalfe’s n² formula, but for value destruction.

A RAND podcast with Bruce McClintock and Doug Ligor got me thinking about this. Their analogy: imagine a highway where nothing ever gets removed. Every accident stays there forever. That’s low Earth orbit.

The numbers are stunning: there are somewhere around 130 million pieces of debris, but we can only track about 40% of those. At 17,000 mph, a paint chip acts like a bullet. Last August, a Chinese rocket broke apart, creating 700+ trackable pieces. The ISS has had to dodge debris about 40 times since its launch in 1998.

We’re running a 21st-century commons on 1967 rules. The Outer Space Treaty is 2,500 words—shorter than most app terms of service. Meanwhile, we’ve gone from two countries launching space tech to 80+, with SpaceX alone launching 180 times last year.

The current collision-avoidance system? Satellite operators email each other to figure out who moves. It’s air traffic control via Gmail. (NRB)