Unknown Author | December 2, 2025

The Shadow Army Edition

On proxy warriors, deniability, and knock on effects.

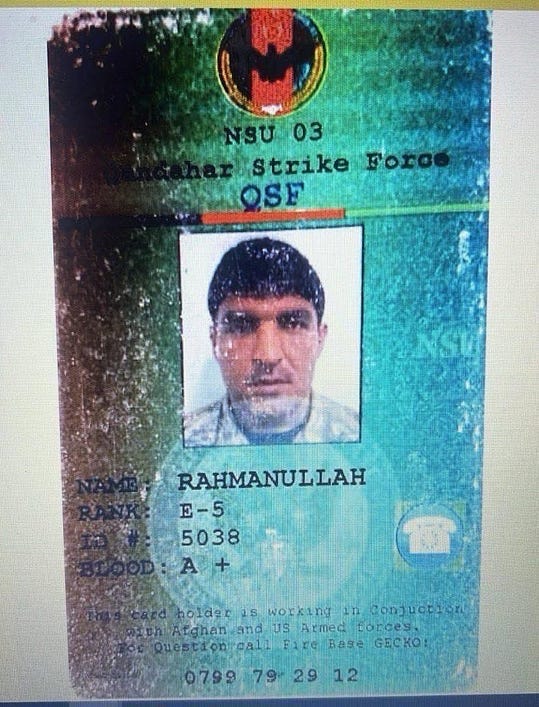

Colin here. The headlines around the D.C. shooting have centered on the usual questions: vetting, motive, security lapses. But buried beneath the bureaucratic phrasing and the slow roll of information is a more revealing thread: the alleged shooter wasn’t just an Afghan evacuee. He was part of a covert paramilitary unit trained and directed in Afghanistan, the kind of quiet activities the U.S. rarely acknowledges.

NDS-03, known as the Kandahar Strike Force, was one of several elite Afghan teams built to do the things the U.S. military couldn’t do publicly, or couldn’t do fast enough. These were direct-action forces: night raids, ambushes, targeted killings, and sensitive site exploitation. They operated hand-in-glove with a range of American units. They did a lot of hard, deniable work and then, almost overnight, vanished from public memory.

There’s precedent for this. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. ran the Phoenix Program, an intelligence-driven campaign aimed at dismantling the Viet Cong’s infrastructure through targeted raids, interrogations, and “neutralizations.” The details are still debated, but the design principle matters: America has a long history of building local paramilitary partners for deniable work in irregular wars. Phoenix was an early template; Afghanistan’s NDS units were a modern continuation of that lineage, just with night vision goggles and better kit.

Why is this interesting?

Shadow armies don’t disappear when the war ends. For years, America fought by proxy through elite, trained local fighters whose names will never appear in textbooks. When the evacuation came, many of these men were rushed out via side doors under “special interest” lists, but without a longer-term plan for what came next. We took highly trained, potentially traumatized, highly loyal irregular fighters, people shaped by years of high-intensity combat and covert operations, and dropped them into American malls, gig-economy jobs, and DMV lines.

If we step aside from the current tragedy and act of domestic terror, the broader argument is not moral, it’s structural. If you build deniable forces, you inherit the deniability. But when the operation ends, the human beings remain. The U.S. had no equivalent to demobilization, decompression, or psychological screening for these units. Those that remained were hunted by the Taliban. Others slipped quietly into the American interior with limited support and even less of a clear identity beyond the work they once did. They worked gig economy jobs, and many have successfully assimilated to a new place. In this case, as details emerge, one committed a grievous act of violence. Nothing about this systemic failure excuses this fact, yet it reveals a structural blind spot.

Zoom out and a pattern emerges. Great powers build paramilitaries to fight their messy wars, and rarely plan for the broader echoes and afterlife of those units beyond bureaucratic checkboxes. The details and backstory of this particular tragedy are still unfolding, but it’s a stark reminder that the tools of statecraft have second and third-order effects; they often outlive the missions that created them. And as history has shown with many such shadow armies, they resurface in ways that are often hard to anticipate. (CJN)