Chris Moon | June 10, 2025

The Rocking Out Edition

On suiseki, bonsai, and stones that look like mountains.

Chris Moon (CM) is a serial hobbyist living in San Francisco. When he’s not practicing the Irish tin-flute, he is making stick chairs, aging umeboshi, or hacking visitor badges.

Chris here. When my wife and I were married, we received a fledgling bonsai tree as a wedding gift from friends. For weeks, we were diligent about delicate watering, proper sun exposure, and general preening. Eventually, during our mini-moon, we were forced to leave the tree alone for three days. Upon our return, it was stone cold dead, a withered husk wreathed by crinkled leaves strewn about its diminutive base.

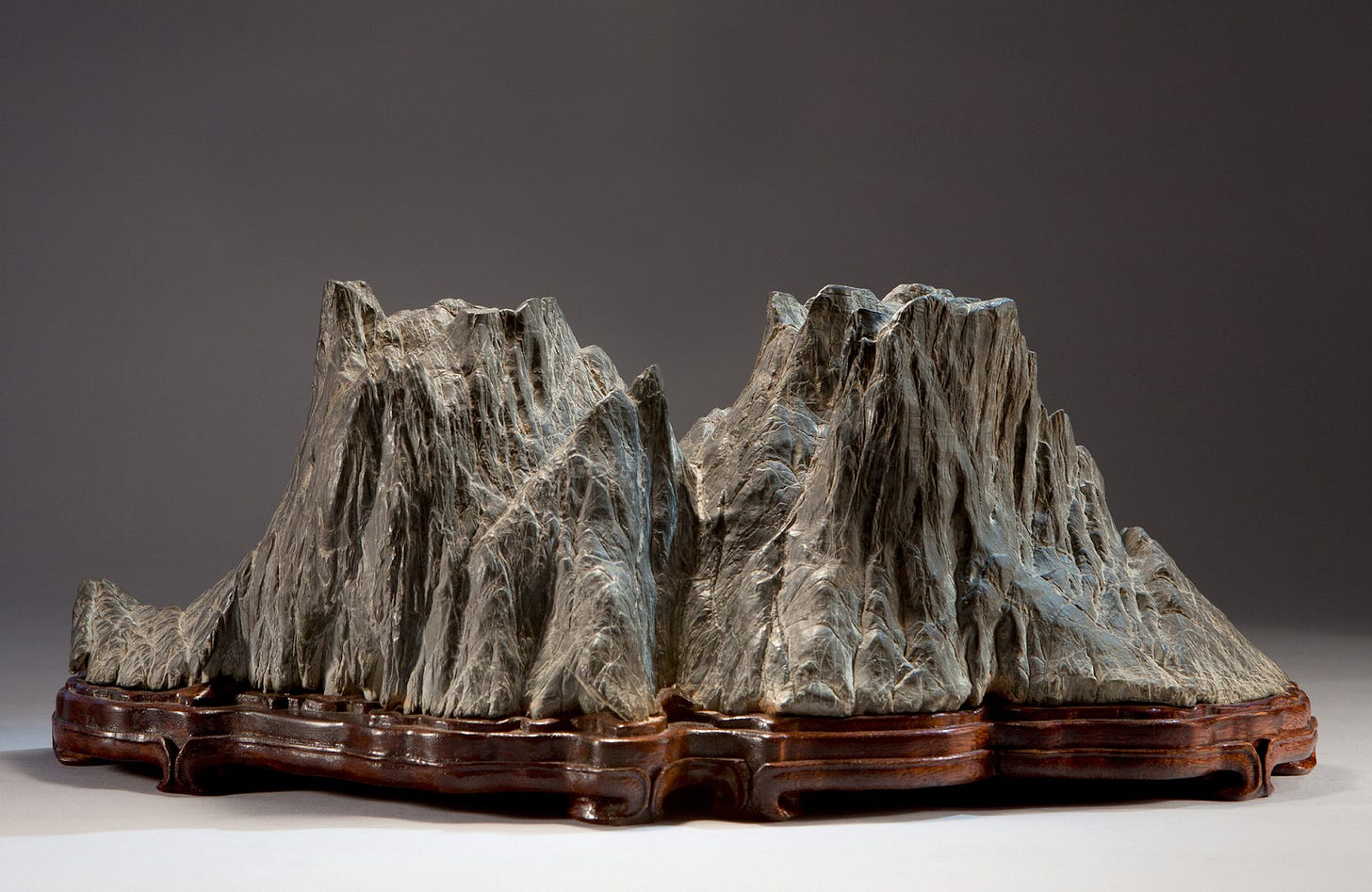

Recently, while on a hike with these friends, my wife and I fessed up that we had, in fact, been awful bonsai stewards. To make amends, I proposed that we hunt for an alluring and expressive stone as a replacement. Eventually, we settled upon a jagged piece of serpentine; it stood like a small mountain, its facets suggesting airy peaks.

Why is this interesting?

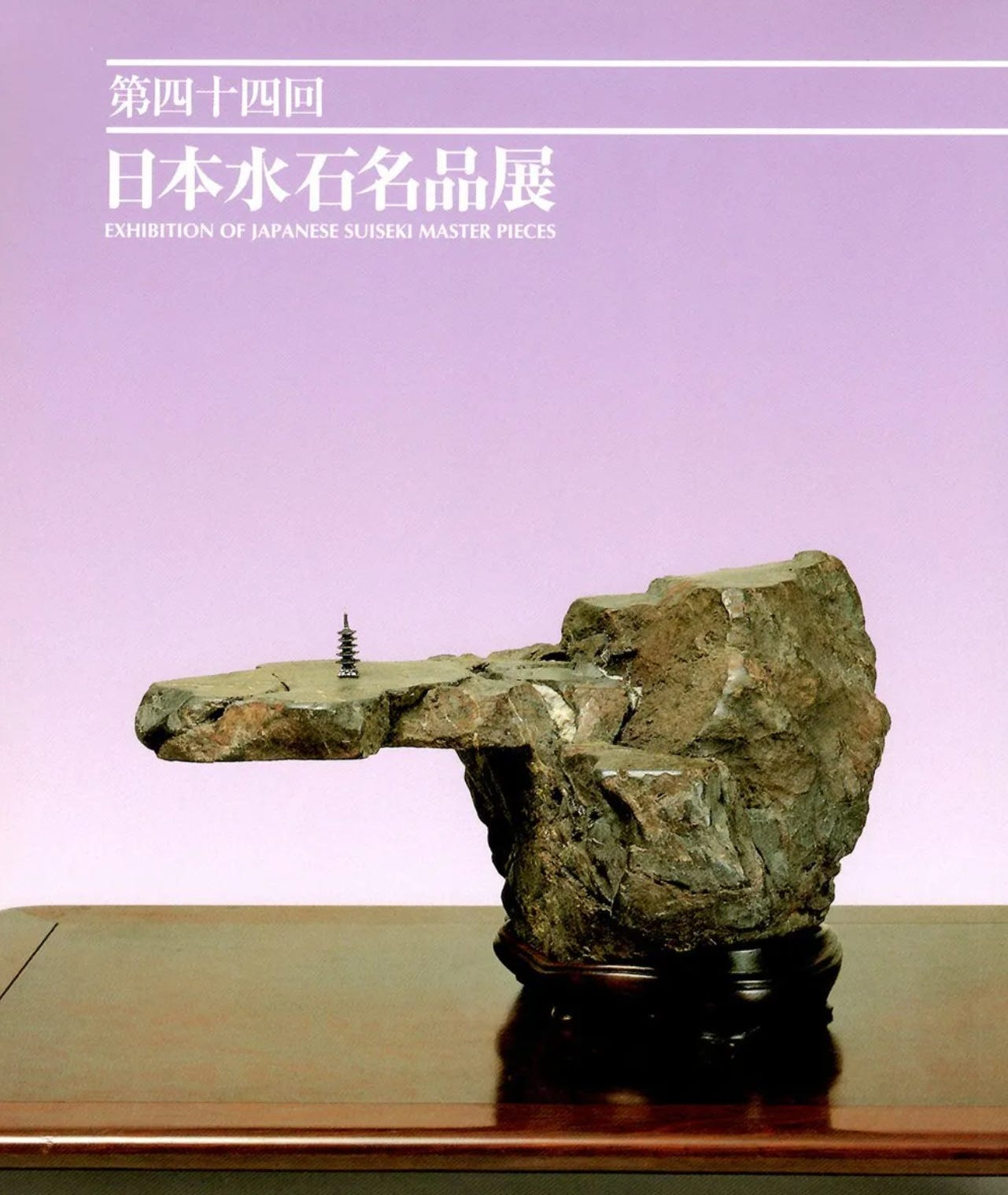

If one has observed traditional Japanese tokonoma displays, they may have spotted suiseki—or ‘viewing stones’—often paired in conversation with bonsai.

Suiseki, the Japanese art of collecting and displaying viewing stones, is centuries old, and originated in China. There, the art form is known as gongshi (“scholar’s stones”) and seeks to provide viewers with stones selected for their tasteful asymmetry, evocative textures, and even resonance when struck.

In Suiseki, the stones are similarly chosen for their majesty and evocative qualities, representing landscapes and objects. Much like bonsai, the presentation of these viewing stones is part of their narrative allure. Known as daiza, their bases seek to present the stones in various ways: nestled in sand, perched in custom dishes, or placed in specially carved wooden bases, the stone’s natural grooves gracefully seating in the recess.

To present my own stone, I chose a piece of figured walnut, and have taken to painstakingly fitting the stone to its new base. Carving with my chisels, I stop to check fitment, and to contemplate the best way to invoke a sense of “toyamaishi” (a distant mountain).

A suiseiki is traditionally a part of a set, and alongside its base is its storage box (kiri-bako), which often includes the stone’s place of origin (such as the Kamo river), and lineage of historical provenance. Having a complete set commands a premium for collectors, with a recent furuyaishi stone fetching $38,000 at auction.

Every year in February, alongside the world famous Kokufu-ten bonsai exhibition, the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum showcases masterpieces of suiseki at the Meihin-ten.

If bonsai is a meditation in shaping and stewarding a vignette of nature’s grandeur, suiseki asks the viewer to contemplate nature’s humble bedrock with a renewed sense of awe. Plus: you can’t kill a rock. (CM)