Jason Boog | December 4, 2025

The Digression Edition

On Montaigne, Tristram Shandy, the compound point, and WITI itself.

Recommended Products

A book that examines the literary scene during the Great Depression and its echoes in today’s world, authored by Jason Boog.

A book that explains how a small creative 'swerve' in thought reshaped culture and set off a chain of historical collisions.

A 2023 translation of Montaigne’s essays, offering a fresh take on his timeless reflections on life and digression.

Fast prototypes are great. Production-ready software is better.

Aboard uses AI for speed, expert engineers for reliability. Custom business applications—CRMs, inventory systems, workflow tools—built specifically for how you operate. Deploy with confidence, not crossed fingers.

Jason Boog is the senior manager of editorial Fable, a social reading platform for book clubs. He is also the author of The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today, and contributor of The ECM Sound Edition and The Cyranoid Edition for WITI.

Jason here. Imagine you are a writer with the misfortune of scribbling in the 2020s, where the AI faucet has overflowed the content bathtub and wrecked the shabby apartment you’ve been renting your whole career. Everything you write feels a bit more disordered, and your old stories wither on search result pages untouched by sunlight. Looking back, you see that your writing life never really had a coherent narrative arc; it was more like a series of detours through different opportunities and obsessions.

You spend a few months reading The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Laurence Sterne’s comic novel self-published in the 1760s. The titular character is attempting to write his memoir, but keeps getting distracted every few pages until the process of failing to write his own story has filled nine volumes. As epic diversions into literature, philosophy, science, and history derail his personal narrative, the hapless narrator exclaims: “Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine;— they are the life, the soul of reading!”

Inspired by that line, you start to find digression lurking everywhere, from your beloved card game to your favorite jokes. Collecting all these examples of swervy writing, you struggle to find your own point. But then you realize that digression is the foundation of this very Substack newsletter, a digital chapel where different writers (who also share the misfortune of writing in the 2020s) bring daily offerings;— We write a couple paragraphs, and then we invoke the trickster god of digression with this prayer:

Why is this interesting?

WITI writers all follow a custom version of a format invented by the French philosopher Montaigne. Back in the 1570s, he called his digression-laden writings “essays,” a play on the verb “assay,” or the act of trying something out. Montaigne began with a single subject like idleness, the education of children, or dreams, but then zig-zagged all over the place. “If [my thoughts] are not directed to and copied by a specific subject which concentrates and leads them on, they will go their own sweet way, skipping hither and thither,” Montaigne writes, in a 2023 translation.

Montaigne has inspired authors for centuries, but his style is completely antithetical to the calcified essay format that we all learned in school. Bots have already mastered every academic essay structure, but digression can take us someplace new. Nobody thinks exactly like you do, Montaigne reminds us, so why not write about all the weird things you’re thinking about?

Virginia Woolf weaponized digression almost 100 years ago in A Room of One’s Own. You may have encountered this book-length essay in school, but it is worth rereading to appreciate the revelatory prose underneath her argument that women deserve both time and space to be creative.

Structurally, the whole story is a literal digression, as the frustrated writer repeatedly strays from her path, kicked out of the library and shooed off the hallowed university grass because she’s a woman. “I will write how I think,” she declares, refusing to follow the patriarchy’s directives.

She concludes by asking the reader to imagine a future writer 100 years hence, who is free to let her mind wander wherever she wants and write about whatever she thinks is interesting:

“She had a sensibility that was very wide, eager and free. It responded to an almost imperceptible touch on it. It feasted like a plant newly stood in the air on every sight and sound that came its way. It ranged, too, very subtly and curiously, among almost unknown or unrecorded things; it lighted on small things and showed that perhaps they were not small after all.”

We should all follow her example.

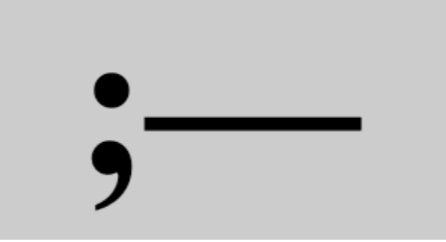

Punctuation of the day:

I also want us to resurrect the “compound point,” an obsolete punctuation mark used hundreds of times in Tristram Shandy, and once by me above. It works like a record scratch for the reader, signalling that thematic curves lie ahead;— since AI models have hijacked the em-dash, using it like a putty knife to spackle over conceptual holes, we need this Shandy Semicolon to signal the untamed human-ness of our own thoughts. (JB)

Quick Links:

Stephen Greenblatt saw digression as an historical force in The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, showing us how a creative turn can reshape a culture: “Everything comes into existence, being as a result of a swerve. The swerve is only the most minimal of motions, but it is enough to set off a ceaseless chain of collisions. Whatever exists in the universe exists because of these random collisions of minute particles.”

Earlier this fall, I learned about the existence of Hinton cubes, a mind-exploding topic that gets a fascinating treatment over at the Public Domain Review.

Tristram Shandy also inspired a simple cocktail, a tasty beverage digression for the day. I recommend making a Shandy when things warm up again.